Written by Michael Smythe LifeDINZ

DINZ Interview

Prince Philip - design champion

Industrial designers usually go unheralded because the better their work the more they are taken for granted. Prince Philip understood the value of good design and endeavoured to have the profession recognised in New Zealand.

Royal involvement in improving the products of industry dates back to at least 1843 when Queen Victoria’s husband and consort, Prince Albert, began his 18-year stint as President of the 89-year-old Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce. Prince Albert’s legacy includes the Great Exhibition of 1851 and the upgraded South Kensington facilities that became the Royal College of Art and the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Queen Elizabeth II’s 25-year-old husband and consort, Prince Philip, would have been very aware of the UK Council of Industrial Design’s post WW2 “Britain Can Make It” exhibition in 1949, and the Festival of Britain two years later. In 1959 the CoID launched the Duke of Edinburgh’s Prize for Elegant Design, which became the Prince Philip Designers Prize in 1990. Philip chaired the judging panel up to 2011 when, in his 90th year, he reduced his workload.

HRH Prince Philip’s first foray into improving New Zealand’s design standards came in December 1965 when, as chair of the Royal Mint Advisory Committee in London, he responded to the Francis Shurrock designs selected and submitted by the Coinage Design Advisory Committee of the New Zealand Decimal Currency Board. Singling-out the 20-cent proposal for constructive feedback, Prince Philip said: “We can’t, repeat can’t, believe even rugby footballers would like to see this on a coin.”

Robert Muldoon, Under Secretary for Finance in charge of the change, may, or may not, have been responsible for the attempt to put the prince in his place by calling on the obvious expertise of the chairman of the New Zealand Rugby Council, Tom Morrison, who stated that the 20-cent design depicted “the true New Zealand rugby player”.

From 2 Februrary 1966, a media leak made the decimal coin designs a front page issue — the New Zealand Society of Industrial Designers (now the Designers Institute of New Zealand) declared the selected designs “childish and banal”. A few days later Mr Muldoon was in Melbourne praising Stuart Devlin’s Australian designs as “without doubt among the most striking in the world”, while suggesting New Zealanders did not particularly care about the design of their coins as long as they had enough of them. Nevertheless, a new design process was commissioned.

15 years later, Prime Minister Robert Muldoon spoke at the inaugural presentation of the Prince Philip Award for New Zealand Industrial Design — hurriedly arranged by the New Zealand Industrial Design Council to align with the 1981 royal tour. The final stage of the selection process had been chaired by Prince Philip himself. His speech to the audience, who were enjoying luncheon at Trillo’s Downtown, lamented the lack of recognition of the designer’s role:

“As far as the development of human civilisation is concerned, design has obviously played a very important part. After all, everything that was not designed by the Almighty has been the responsibility of some sort of designer.”

Behind the scenes, Prince Philip was adamant that awards in his name should be received by the industrial designer of the winning work, rather than an engineer or the company manufacturing it. Reflecting on the winners of the Prince Philip Award for New Zealand Industrial Design offers a small insight into our capacity to make the most of our world-class design and innovation.

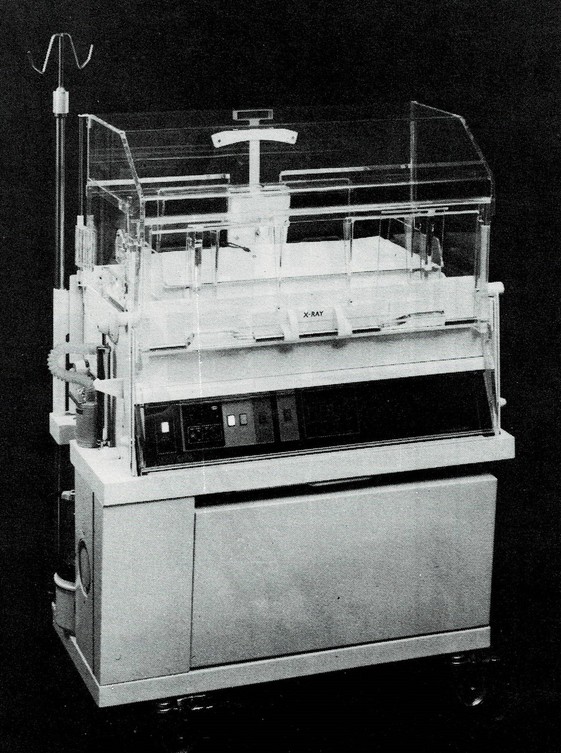

1981 — Premicare baby incubator designed by Paul Martin. The 1969 version had been awarded a Designmark and went on to win the 1977 UDC Inventor of the Year Award and the 1978-79 NZ Plastics Premiere Award for Elegance of Design. By 1981 prototypes featuring a state-of-the-art microprocessor control and monitoring system were being tested. Paul Martin was not at Trillos to receive his award. In a scenario that remains a familiar fate for great New Zealand innovations, he had moved to the United States to work as a consultant to the United States company who, unlike local investors, were willing to take on the manufacturing, marketing and continued evolution of the product. (Data Medical, the company Martin established with Clearlite Plastics and the Development Finance Corporation, sold the Premicare product to baby monitor developers Healthdyne Inc. who were expanding their range.)

1982 — PDL 56 Series plug and socket range designed by an in-house team led by the Director of Engineering — there was no industrial designer named. The range featured versatile modularity, patented self-sealing and locking transparent socket covers, transparent plug bodies allowing easy inspection, ease of installation and maintenance, and a strong, clean aesthetic. 40-years on the 56 Series is still manufactured. (PDL by Schneider has been a product brand since the company was sold to France-based multinational Schneider Electric in 2001. There is no evidence that any product development or production functions remain in New Zealand.)

1984 — Fisher & Paykel refrigerator range designed by a multi-disciplinary team. Project leaders Dean Joiner, GM, and Murray Higgs, Marketing Manager, appreciated the integrative role of the three industrial designers: Bruce Gibson, John Hatrick-Smith and Mark Elmore. The products were subsequently marketed as “the Award Range”. The visually simple and innovatively manufactured refrigerators still look at home in a modern kitchen despite being 30+years-old. (Fisher & Paykel Appliances is now owned by Chinese company Haier while its expanded design-led R&D resources remain in Auckland and Dunedin.)

1985 — Tait Electronics T500 two-way radio designed by a multi-disciplinary team led by industrial designer Steve Allan — the first time a non-engineer had been a designated project leader at Tait. Along with electronic advances, the innovations included an ability for ten people to assemble the product much faster than the 42 required for the previous model. Sales exceeded 500,000 units — five times more than predicted. At the event it was the more senior engineering manager who was handed the award by Prince Philip, presumably during the February 1986 royal tour. (Tait Communications remains New Zealand owned and retains R&D and manufacturing resources at its Christchurch headquarters.)

1989 — Formway Zaf chair designed by a multi-disciplinary team led by industrial designer Mark Pennington. While other office furniture manufacturers responded to the post-GFC slump by cutting costs, Formway Furniture focused on ergonomics and quality which paid off in increasing the productivity of well-supported end users. The Zaf chair became the chair of choice for fitouts from the banks to the Beehive — and Prince Philip ordered two. (Formway is now a design and development company licensing designs to global manufacturers. Formway recently established the Noho manufacturing plant in Taita to produce its Move chair which is marketed and distributed globally.)

The New Zealand Industrial Design Council’s 20-year lifespan came to an end in 1987 at the hands of the Rogernomic’s driven Great Quango Hunt which required quasi-autonomous government organisations to become self-sufficient. (The same fate did not befall the British Design Council which remained fully government funded in the face of Thatchernomics.) Responsibility for industrial design was transferred to Telarc (the Testing Laboratory Registration Council) where Designmark and the Prince Philip Award eventually died of neglect.

Since 1992 the design profession itself, through its Designers Institute of New Zealand, has recognised design leadership through The Best Awards. The supreme accolade, the John Britten Black Pin added in 1995, acknowledges the value of a specific designer’s work over time. It equates with the Prince Philip Designers Prize, administration of which was taken over by the UK Chartered Society of Designers in 2011.

It will be interesting to see if another member of the Royal Family follows in the footsteps of Prince Albert and Prince Philip. In the meantime, there is good reason to reflect upon the value of the Duke of Edinburgh’s legacy as a champion of the best designers enhancing human existence.

© Michael Smythe, 15 April 2021

POSTSCRIPT - 27 April 2021:

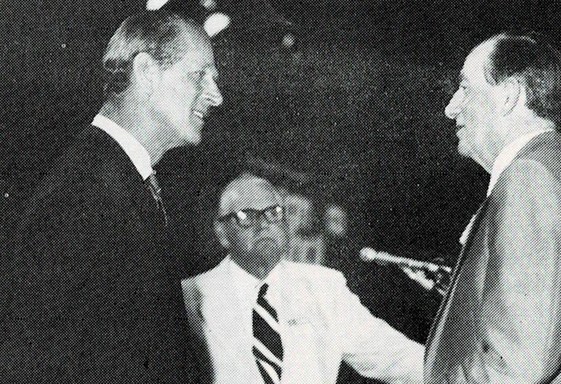

When the Designers Institute published this article online on 21 April (the day of the New Zealand memorial service for Prince Philip) it jogged some memories. Professor Jolyon Saunders (industrial design educator at the Elam College of Fine Arts from 1962) recalls meeting Prince Philip at the 1981 event. “He was disappointed that he hadn't met with local design leaders. The occasion fell rather flat.”

This was remedied in 1974 when the Duke of Edinburgh was in Christchurch for the Commonwealth Games. During a visit to the Crown Crystal Glass plant at Hornby the CEO, Ian Lyons, introduced him to Elam graduate industrial designer John Densem (1942-1989). Prue Densem found this photograph in her late husband’s album and sent it through.